Imagine the perfect alien invader. It would likely be from somewhere far away with characteristics beyond our wildest imagination. Venomous spines would protrude from its back, protecting it from predators. It would have a voracious appetite, gobbling up everything in its path. This alien would also be able to reproduce at an alarming rate – spawning hundreds of thousands of eggs every couple of days. This alien invader has one single weakness – it’s delicious. Meet the invasive Indo-Pacific lionfish.

Why are lionfish a problem?

The invasion began with just a few individual fish, likely released from aquaria in southeast Florida. The first sighting was reported off Dania Beach in 1985, and the population began skyrocketing in the 2000s. Their range expanded up the Atlantic coast of the U.S., east to the Bahamas, and south throughout the Caribbean. By 2010, these invaders had made it to the northern Gulf of Mexico, where some of the highest densities of lionfish can now be found. To put this in perspective, imagine seeing more than a hundred sharp, venomous swimming objects packed into a space roughly the size of a small bedroom – this is now what you can find off the Florida Panhandle. The total number of lionfish is currently unknown, and very difficult to estimate.

The question remains: why are lionfish such a problem? They are essentially the perfect alien invader. First of all, you can find lionfish pretty much anywhere. They have been found everywhere from mangrove habitats, estuaries, and seagrass beds; to coral reefs, limestone ledges, and artificial reefs. Additionally, they are equipped with high reproductive capabilities – a single female can spawn millions of eggs per year. These factors, combined with a venomous defense system, make for a highly successful population of alien invaders.

The main concern for native species is that lionfish are opportunistic predators, consuming more than 150 different native fish and invertebrates. These native prey include economically valuable species like juvenile snappers and groupers to ecologically important ones like small crabs and wrasses. Many of these prey have not adapted to protect themselves from lionfish. Their cryptic coloration helps camouflage them within their surroundings as they herd their prey slowly with their large, feathery pectoral fins before slurping them up in a fraction of a second. Not only are they directly consuming large numbers of prey, but they are competing with native predators as well. The alarming number of lionfish, their rate of range expansion, and their large appetite constitute this highly invasive alien threat. Scientists have documented decreases of up to 79% in juvenile fishes in just six weeks due to lionfish predation. Lionfish are one of the hottest topics in marine fisheries research today, but more needs to be investigated to fully understand the negative effects of the invasion.

How do we control them?

Many Florida seafood markets and grocery store are now selling this invasive, venomous predator. Don’t worry – “venomous” has a different meaning than “poisonous.” You must be injected with venom for it to take effect – similar to a snakebite. Poison needs to be ingested to be effective – like the bladder of a blowfish, known as fugu. Lionfish are equipped with 18 venomous spines along their back and belly, but the white, flaky fillets are poison-free and absolutely delicious. There are videos online on how to safely handle, harvest, and fillet lionfish to avoid getting stung.

Eating invasive species is certainly a creative tactic for attempting to keep their populations in check. However, as with unappetizing pythons and poisonous cane toads, this isn’t always a potential solution. In the case of lionfish, it may actually be making a difference.

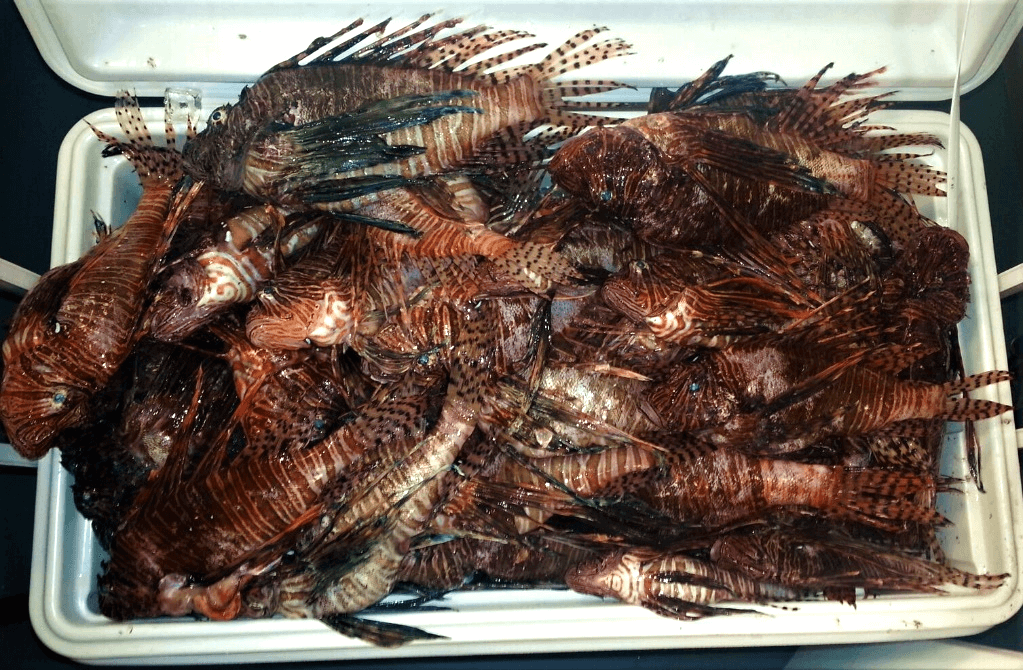

Specialized spearfishing tournaments have been happening for over a decade now, designed to encourage divers to remove as many invasive lionfish as they possibly can. Lionfish are difficult to target with traditional hook-and-line gear, though you can occasionally catch one with light tackle and small live bait. It is much more efficient to dive down and spear them by hand. Several of these lionfish “derbies” occur annually, with many of them centered on Florida’s annual “Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day” in May. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission declared this event through a resolution to encourage lionfish removal by divers, and it has resulted in over 60,000 lionfish collected in the past five years on that weekend alone. Unfortunately, tournaments are limited to weekends with calm winds and good weather. Another downside is that the cash prizes can be less than what the divers could receive by selling their fish.

In order to sell lionfish, divers need only a $50 annual Saltwater Products License (SPL). Diving and spearfishing can be expensive, but oftentimes divers are able to cover the cost of their trip and make a few extra bucks by selling their lionfish to local markets. They can get paid anywhere from $4-7 per pound of whole, unprocessed lionfish. Many seafood dealers are willing to participate due to the increasing demand for this exotic fish. Fish markets, restaurants, and stores such as Whole Foods will display the entire fish intact for an eye-catching seafood choice inside the cooler or on the plate.

The price for the consumer ranges anywhere from $9.99 per pound whole to $27.99 per pound for fillets, or as much as $40-50 for a high-end restaurant entrée. It may seem high for such a small fish, but with enjoyable taste and texture similar to the highest quality groupers and snappers, the price is just right.

An additional profit can be made from the leftover parts of the lionfish. Lionfish spines, fins, and tails make perfect materials for jewelry. This is especially important for lionfish control and profitable removal in areas that are affected by ciguatera toxins, such as in some Caribbean regions, which can render affected fish inedible.

The unfortunate truth is that even with sustained control efforts, tournaments throughout the year, and an established commercial industry, lionfish are likely a permanent addition to Atlantic, Gulf and Caribbean marine ecosystems. Local removal efforts have proven to be effective at keeping the populations at reduced levels, and perhaps we can sustain this on a larger scale. Some commercial lionfish hunters have already noticed that lionfish are becoming more difficult to find at their “honey holes,” and the densities overall have seemed to show a stark decline in the past year. However, it’s a big ocean, and complete eradication is highly unlikely. The good news is that the tasty weakness of this alien invader has led the diving community to take these lemons and make some delicious and profitable lemonade.

Created By: Meaghan Faletti for FLocal Media

About the Author: Meaghan Faletti is a graduate student at the University of South Florida, and is currently researching hogfish. She is passionate about marine ecosystems, running, and traveling. She lives with her fiancé, Travis (@flatlinespearguns), and her dog, Brody (@adventuresofbro).

Videos:

Tips for Lionfish Removal

How to Fillet a Lionfish

Lionfish Hunting in Apalachicola